The Town Hall fire

The details for this account of the Nambour Town

Hall fire were taken from the Nambour Chronicle of 25-10-1929, page 9.

Most towns that sprang up in south-east Queensland in the early days were composed of buildings built of locally cut timber. Only those settlements that developed in areas where suitable building stone was readily available contained buildings of a more substantial and permanent construction. The flammable nature of wooden walls and roofs mixed with kerosene lights and candles provided the ingredients for the common fires that often, as in Nambour's case, caused widespread havoc, leading to anxiety in the civilian population.

The public concern about the quality and safety of towns and their buildings was reflected by the Queensland State Government, which in 1923 introduced the ‘first instalment in town planning powers.’ This was followed by amendments to the Local Authority Act 1902 – 1924 which allowed the declaration of ‘First Class Areas’ under Clause 185 of the Act. Under this amendment councils were "given control over construction materials and other aspects relevant to fire prevention. They could regulate the classes and types of buildings that could be constructed, the building materials that could be used, and could stipulate the size of blocks and the height and alignment of buildings."

As a result of Nambour's disastrous fire of 5th January 1924 which burned down 17 shops in Currie Street, and to prevent the owners from rebuilding their premises using similar hazardous materials, the Maroochy Shire Council took advantage of the State Government’s legislative amendments by requesting that the Government proclaim that the business precinct of Currie Street from Bury Street to Petrie Creek be declared a ‘First Class Area’. This meant that any replacement buildings or extensions needed to be built in brick or concrete, Chadwick Chambers and Collins Building being the first to arise from the ashes in compliance with the new requirements.

By 1924 the Maroochy Shire Council had outgrown its Town Hall, and the appointment of a Shire Engineer made the need for additional space imperative. A new addition was therefore added that June to the southern side of the hall and, as the Town Hall was in Currie Street, it was built of brick. This new section, costing ₤900, had two storeys to match the rest of the building, and was topped with a gable roof. This gable was behind and at an angle to the two original gables at the front. Each storey had a large room, in which was incorporated a brick strongroom. The two strongrooms were therefore built one above the other. {18-7-1924, p.9}

The upper room made provision for the Shire Engineer to have his own room, and in fact all Shire office staff were now able to be accommodated in the first floor chambers. The strongroom on the top floor was in the Shire Clerk's office. It was made to house all the Shire's record books, account books, ratepayers' details and any cash on hand. One of the new rooms on the ground floor was let to the local solicitor Mr Alex. W. Thynne, a co-proprietor of the Nambour Chronicle. Mr Thynne kept all his clients' papers, official documents, and all the records of the Hospital, Chamber of Commerce and the Showground Trust in the brick strongroom attached to his room. He had moved to the Town Hall after his office in Howard Street was destroyed in the great fire of 5th January 1924. In 1925 the Nambour Town Library had grown to over 4000 books, so it was moved out of the Town Hall into a new adjoining building. {11-1-1924, pp.7, 8} {18-7-1924, p.9}

In the mid-to-late 1920s, the Town Hall was refurbished. Internal alterations were made, and electricity connected in late 1927. Though its interior had been left as natural wood since it was constructed, the whole building was painted inside and out at this time. The rents for the offices, shops and auditorium had been kept low, and in 1928 they had only raised ₤679 for the Shire. By 31st August 1929 the Town Hall Account was overdrawn by ₤224. {20-4-1928, p.1} {31-8-1928, p.9} {20-9-1929, p.2} {27-9-1929, p.3}

The Nambour Town Hall, built in 1913, lost to fire in 1929.

Photograph courtesy Sunshine Coast Libraries

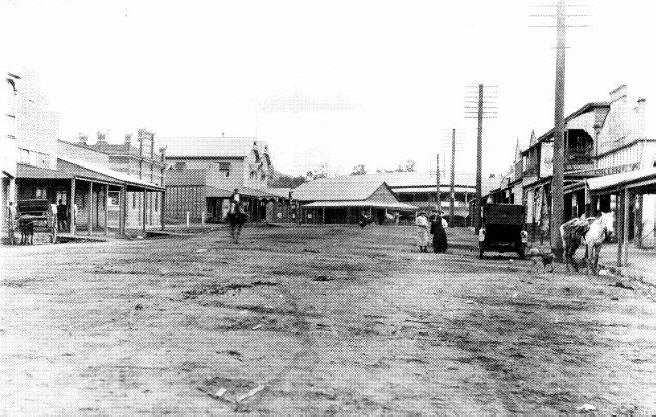

Looking north up Currie

Street from near Howard Street in 1920. The Club Hotel is to the left of the

camera, and the building

where the 1924 fire started is to the right. In the centre background

behind the horseman is the twin-gabled Nambour Town Hall, with Kent's building to its right.

Kent's building was demolished to enlarge Station Square. In 1920 it housed D. Murtagh's Hairdressers (see below). The two-storeyed

Royal Hotel can be seen at the bend in the street. The Nambour Railway Station

is behind the Town Hall.

Photograph courtesy Sunshine Coast Libraries

Kent's Building sits on an

'island' in the middle of Station Square. Station Street goes around it on

three sides. The Nambour Town Hall is out of view to the left, and the Royal

Hotel is at right. The photographer is standing in Currie Street, and the

Railway Station is behind the fence in the background.

Photograph courtesy Sunshine Coast Libraries

A parade led by Scottish Pipers heads south down Currie Street, circa 1921.

Nambour's only brick building, the new E.S.& A. Bank, is at centre. The

Nambour Town Hall is to its right. William Whalley's large Universal Stores

is out of view to the right, on the same side of the street as the

photographer. He owned a number of buildings in the town, including a second

shop to the left of the E.S.& A. Bank.

Photograph courtesy Sunshine Coast Libraries

Nambour Town Hall, with the auditorium used as a cinema.

Photograph courtesy Sunshine Coast Libraries

The site of the Nambour Town Hall in 2008.

The site of Kent's building, separated from the Nambour Town Hall by Station Street, as it appears in 2008.

The site of Station Square in 2008, showing the entrance to Nambour Railway

Station behind.

The Hall's auditorium had been rented out to various picture show operators from 24th February 1915, only eighteen months after it was built. It was first used for three months by a man trading as 'Express Electric Pictures' until April 1915, then by 'Bennett's Pictures' (known familiarly as 'BP') until January 1923, then by the Messrs. Gearside operating as 'Town Hall Pictures' until mid-1925, and finally Mr E. Wells until August 1928. The various lessees used their own electricity generating plants, even after mains electricity was connected to the town in late 1927.

The cinema screen was located at the rear of the hall's stage, while the projection box was placed at the eastern end. The pictures were all silent, so there were no loudspeakers required. As the hall's seating, supplied 15 years before, was unsuitable for relaxed watching of films, the lessees had to provide enough rows of canvas chairs to accommodate a capacity audience. The Council was not altogether happy with this arrangement, and the Nambour Chronicle of 20th April 1928 described moves by Shire Chairman Cr. J. T. Lowe to have more modern seating installed. The leases were re-negotiated approximately every three years, and usually a new lessee won the contract to show pictures.

A returned Digger, Mr Michael Harcourt Gray had leased the Diggers' Hall from 1924, and installed his Biograph equipment there. He operated it as the Empire Pictures until it was destroyed in the disastrous fire of 26th June 1928. As the fire, starting next door, had taken two hours to endanger the galvanised-iron clad Diggers' Hall, Mr Gray, with willing help, had been able to rescue most of his equipment before the roof fell in, including 200 canvas chairs. His generating engine and dynamo had been located in a shed behind the hall, and were undamaged. {21-9-1923, p.9} {21-9-1928, p.5}

He now found himself with projection equipment but no venue. Fortuitously, the lease for the Town Hall cinema came due for renewal two months after the fire. Mr Gray made a successful tender for a five-year lease, outbidding the previous lessee, his associate and friend Mr. Edgar Wells, and installed his equipment in the Town Hall's auditorium. [As Mr Gray and Mr Wells had for the past year or so been working together, sharing film programs to reduce rental costs, it is likely that, with the loss of Mr Gray's Empire Pictures at the Diggers' Hall, they agreed that Mr Gray could take over the Town Hall Cinema, which would allow Mr Wells to devote his time to running his Returned Soldier's Garage.]

The last three lessees had felt that the Hall could be more effectively used for cinematic entertainment by reversing the layout. The Council had not previously agreed to this, but after Mr Gray described the advantages that would accrue, they concurred with his suggestions, and so a projection box was built above the stage, and a larger screen set up high at the eastern end. The projection box was sheeted with galvanised iron, as a fire-safety precaution. As the chairs were all portable so that the Hall could be cleared for socials and dances of which there were on average twelve per year, it was a simple matter to turn them around to face the new screen position. {31-8-1928, p.9}

The projection equipment reduced the stage depth from 30 feet to 18 feet, which caused some criticism. Alterations needed to be made to the proscenium, probably due to the elevation of the projectors. Some people felt that the alterations were "the spoilation of the Hall for general purposes." Backing Mr Gray, the Shire Council stated that 90 percent of the revenue earned by the Hall was by way of motion pictures. The stage, though narrower, was still deeper than those of halls in much larger towns.

The Nambour Chronicle also supported Mr Gray's alterations in its edition of 31st August, 1928, saying "there is a vast improvement in the portrayal of the pictures, which are thrown at a height that enables a focus in a comfortable position." It stated that the new arrangements offered extra seating accommodation, and that Mr Gray had gone to the trouble of installing more modern footlights to the stage, as a gesture of goodwill. The alterations cost the Council nearly ₤162. Mr Gray's lease payments were adjusted so that he would pay ten percent of their cost per year over the duration of the lease. {31-8-1928, p.9}

Although the first talking picture 'The Jazz Singer' had premiered on 6th October 1927, they were still a novelty, even in large American cities. Mr Gray had heard of the process, but felt that the extra costs he was incurring in having alterations made to the Shire Hall were enough expense for the time being. Sound equipment could wait for some future time, which in fact never came to the ill-fated Nambour Town Hall.

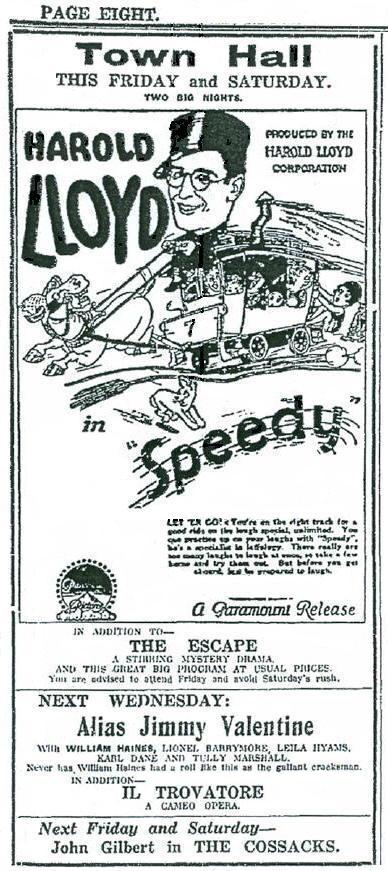

On the night of Wednesday, 23rd

October 1929, over 150 people were at the Town Hall Cinema, enjoying

the latest silent films. (A note regarding Harold Lloyd's film 'Speedy',

shown the previous week and advertised at right, can be found at the bottom

of this page.) They had watched 'Alias Jimmy Valentine',

starring William Haines and Lionel Barrymore, and then enjoyed refreshments

at the interval. Now they were watching a version of the opera 'Il Trovatore' (The Troubadour)

which had just started. {18-10-1929,

p.8}

On the night of Wednesday, 23rd

October 1929, over 150 people were at the Town Hall Cinema, enjoying

the latest silent films. (A note regarding Harold Lloyd's film 'Speedy',

shown the previous week and advertised at right, can be found at the bottom

of this page.) They had watched 'Alias Jimmy Valentine',

starring William Haines and Lionel Barrymore, and then enjoyed refreshments

at the interval. Now they were watching a version of the opera 'Il Trovatore' (The Troubadour)

which had just started. {18-10-1929,

p.8}

The two projectionists, Gordon Myers and Ray Mercer, were in their galvanized iron projection box. It was elevated above the stage and reached by a flight of stairs. As normal silent movies involved many reels of film (usually five, but often many more than that), two projectors were required so that there would be no pause between reels.

The procedure was that, when one projector was nearing the end of its reel, two small signals, usually circles, would flash onto the upper right-hand corner of the screen, a few seconds apart. The projectionist would have the other projector threaded up and ready to go. On the second signal, he would throw a switch that would shut off the first projector and instantaneously start the second, so that the audience was not aware of any interruption in the program.

The light for these projectors was provided, not by a bulb, but by a high-powered electric arc between carbon electrodes, similar to the arc used in welding. The intense light from the arc was focused into a projection beam by a concave mirror behind it. These arc lamps ran extremely hot and needed regular monitoring to ensure that the arc did not vary in brightness. The film stock of the day used a nitrocellulose base, highly flammable and quite dangerous.

While Mr Myers was preparing to load a reel onto the second projector, there was a flash from the other machine. The belt to the take-up spool had suddenly broken and the film feeding out of the projector had been thrown across the hot lamphouse where it ignited at once, spilling loops of blazing film onto the floor all around the projector. In shock, Myers dropped the reel he was holding and as it hit the floor the film sprang out and "within a second all the films were alight." A gasp went up from the audience as the movie they were watching suddenly disappeared and the screen was illuminated instead by the fire in the projection box.

Gordon Myer's presence of mind did not fail him, though, for he quickly pulled the switches that shut off power to the projectors and turned on the hall lights. He tried to extinguish the flames with a box of sand which was kept for that purpose, being a more effective way to smother that class of fire than water. The few seconds he spent in the attempt nearly sealed their fates, as the projection box was now completely ablaze with burning film. Neither he nor Ray Mercer could get past the flames to the box's exit and stairway.

Within a few seconds of the fire starting, the audience, turning in their seats, were aghast to see the fire behind the projection windows. The exit doors were opened at once, and all hurried to safety, although some refused to use the side exits, but headed for the main doors, which were under the screen at the opposite end of the building from the fire. The proprietor of the cinema, Mr Michael H. Gray, was in attendance. Seeing the outbreak, he rushed to the projection box and opened the door, but was driven back by the flames. Mrs Gray rushed out to the street with the rest of the audience, and Mr Gray later spent some anxious minutes before he was able to locate her.

Trapped, Gordon and Ray desperately began to punch and tear at the galvanized iron sheeting at the front of the projection box with their bare hands. Suddenly the iron gave way, and Gordon fell out of the box down to the stage floor. Ray was in the box a little longer and suffered severe burns. He jumped and hit the floor hard, and joined the audience as they rushed to the exits. Later, both men needed ambulance attention. Gordon suffered severe lacerations and cuts to his hands and arms, and serious burns. Ray Mercer's burns were so dire that he was admitted to hospital. The damage to the projection box released the flames into the auditorium. Within four minutes of the fire starting, the Nambour Town Hall with its cinema, three shops, and Council Chambers was a raging inferno from end to end.

Mr R. S. Melloy, an auctioneer, rented one of the shops on the ground floor, with street frontage. He was in his office at the time of the outbreak, engaged in a "knotty problem" with accountant Mr H. C. B. Murray. All at once "the glare attracted their attention. In a moment almost, they noticed the flames licking through the walls from the hall side. Mr Melloy grabbed his books, which were near at hand, and made a dash for the front, but here his progress was barred by the audience struggling to get out. He found his way to safety through a side door. This led to a laneway between the Town Hall and the Bank of New South Wales, where his new Chevrolet car was parked. He quickly deposited the books on the other side of the road, and ran back for another lot, but by this time he could not reach his office or his car. All his stock was destroyed and the car, many personal effects and other valuables were lost."

Mr Alfred Crofts also rented a shop at the front of the Town Hall. It was a chemist's pharmacy, and he had operated a shop there for 30 years, since 1899. The first fourteen of those years had been spent in a little shop on the same site, before the Town Hall was built. His son Kingsley worked with him as an assistant, and was known around the town as a keen motorist. Kingsley was in the cinema, enjoying the movie, when the fire broke out. He later said, "I was sitting in the pictures, not very far away from the door, when I noticed the reflection of the burst of flame on the screen. For a moment I could not understand the meaning of it. As the flames shot up I then realised what it meant, and I made a dash for our premises. I rushed into the shop but was only able to snatch up a few account books and a number of prescription books before I found that the flames were almost upon me from all sides. I had to beat my way out, and in doing so my face and hair were scorched. For a moment I thought it was all up, but then made a rush for it." {19-12-24, p.5} {25-10-29, p.9}

Solicitor Mr Alex W. Thynne, who was working in his office when the fire was first noticed, was driven out by the heat and the crackling of the flames. He packed up hastily and placed all of his valuables in his strongroom, locked it, and departed. As the front door was blocked with people, like Mr Melloy he had to make his escape through a side door into the laneway. Mr Thynne had previous experience with fires, his office in Howard Street having been burned down in the great Nambour fire of 1924.

[ It is worth remembering that Nambour would not have a Fire Brigade with paid firemen until 1948, and a reticulated water supply would not be connected until 1959. At the time of this fire there were only volunteers to put out fires, running around with buckets of water from rainwater tanks.]

The cinema goers and other people who hurried to the scene saw at once that the Nambour Town Hall was lost. A wind from the south directed the fierce heat across Station Street mainly to Kent's building, and to a lesser extent across Currie Street to William Whalley's Universal Stores, now rebuilt, modernised and renamed Whalley Chambers. Both these buildings had large awnings which directed the heat towards the large shop windows, which immediately began to crack. Soon merchandise was being removed from Mr W. B. Kent's shop by many helpers, while another band was bringing buckets of water to throw over the facade. One of the large shop windows had a display of bicycle requisites. Flames appeared above this window under the awning, and soon all the stock was ruined. As the facia to the awning of Kent's building began to smoke, it was ripped off for the whole length facing the fire.

When the glass in the windows of Kent's building began falling out due to the tremendous heat, it was felt that the shops in it were beyond saving. Attention then turned to the Royal Hotel, a little further away. The sparks from the fire were sweeping over the hotel, so the proprietor told all boarders to pack up and remove their belongings, and the rooms facing the fire were closed up. Cars were driven out of harm's way, and preparations made for a protracted battle.

Suddenly the wind changed to the north, and fanned back the flames. The Royal was safe, but Kent's building, though no longer threatened, was badly charred and "left in a very much disturbed state." The fire was now being driven through the buildings on the south side of the Town Hall. The Bank of New South Wales was soon engulfed, and also the Nambour Town Library with its collection of "over 4000 volumes of excellent and up-to-date books." Soon it was seen that the living quarters of the E. S. and A. (English, Scottish and Australian, now Esanda) Bank officials were in danger, and buckets of water were splashed on the walls.

At Whalley Chambers, a large number of employees, together with the shop principals and other helpers, were engaged in soaking the outside of the building. From the top floor, tubs of water were taken out onto the awning, and spray pumps and buckets from Mr Whalley's stock brought into play. In order to prevent ignition of the lower portion, the canvas blinds were lowered and kept wet. The southern eave of the building did catch fire, but prompt action put it out.

In its report, the Nambour Chronicle wrote: "The work of the fire fighters became most hazardous due to the extreme heat that emanated from the flames. Tongues of fire rose to a tremendous height, and the noise as the twisted iron was flung from the roofs and crumpled up like wrapping paper, was frequently heard. Many of the workers who time after time advanced towards the threatened buildings, were beaten back by the heat, hair and clothing being singed. The menace of the falling sparks rendered the task not to be envied, and placed those who ventured forth in the work of effecting a save in great risk of their lives. Never on any previous occasion of a Nambour fire have the flames become so fierce, reaching such a pinnacle as to require the services of a large hose with tremendous pressure to in any way place them under control.

"At the rear of the Town Hall there is a little café conducted by Mrs Biltoft. This lady knows something of the ravages of the fire fiend, having been rescued with difficulty on the occasion of the great fire in Howard Street, when the same picture proprietor who now suffers an exceedingly heavy loss was burnt out. [In the fire of 26th June 1928, Mrs Biltoft and her daughter were trapped on an upstairs balcony and had to be rescued by ladder.] Their café was only a few feet away from the rear buildings attached to the Town Hall. A band of workers were engaged in this portion, and were uncertain whether or not their efforts were to prove successful. Proceeding with their buckets and doing everything possible to stem the invasion, they at last achieved their objective."

By now the fire was dying down, but some of Nambour's most important buildings had been destroyed. The Council Chambers with its brick addition, businesses, shops, the Town Hall auditorium with its Picture Show, the Nambour Town Library with its reading room, and the Bank of New South Wales were gone forever. However, Mrs Biltoft's cafe, Mr Kent's building, Whalley Chambers and the living quarters behind the brick E. S. and A. Bank were still standing, though badly scorched.

The

ruins of the Nambour Town Hall on the morning of 24th October 1929. Whalley’s Chambers is opposite.

At centre are the still-standing remains of the brick addition to the

building, with the two brick strongrooms, one above the other.

Photograph courtesy Sunshine Coast Libraries

The Nambour Town Hall was completely razed to the ground, except for the brick structure containing the two strongrooms, one above the other, that had been added to the Town Hall in 1924. Council officials were greatly concerned that all their official records in the top strongroom could be lost. This concern quickened to alarm when they saw that solicitor Mr Thynne's strongroom door on the ground floor was firmly closed, but the door on the Council's strongroom above it was slightly ajar. They would have to wait for the site to cool down before they could open the door and find out if anything had survived.

In the light of day, the citizens of Nambour glumly looked over the ruins of their Town Hall. There was virtually nothing left except the crumpled corrugated iron from the roofs. This would later be auctioned by the Council as scrap. The books and documents in Mr Thynne's strongroom were found to be safe, although the brickwork had been cracked by the heat. All of his office furniture was lost.

In the Council Chambers on the erstwhile top floor, the Shire Engineer Mr A. Eckersley had lost all his books and instruments. All office equipment and stores of the Shire Council were destroyed, and many private books and belongings owned by the Councillors and their staff. The Tramway Manager, Mr Stephen Hobson had placed his record books and some private papers in the strongroom, and the fate of those, and the majority of Council records, was uncertain.

A ladder was procured by the Shire Clerk Mr A. H. Brookes, and set up against the brick strongrooms. He climbed up to the top one, where the door was slightly open, and peered in. He called down that, as far as he could see, the interior of the strongroom appeared alright, but the door was jammed. Later in the morning, "the door was prized open, and the strongroom contents, comprising for the most part leather-bound account books, were thrown from out of their confinement and packed into a lorry. Although blackened on the covers and on the edges, the books were intact and will be serviceable. To find them in a state of preservation at all must have been a big relief to the very worried Council official."

A week after the fire Alfred Crofts and his son were advertising 'Business as Usual', and were working out of a shop in Chadwick's Building. Mr R. S. Melloy was working out of the Alhambra Hall, next to the Royal Hotel. Mr Thynne had taken over an office next to the boot department in Whalley Chambers. {24-9-1948, p.6}

The loss of the Town Hall was discussed at the next Maroochy Shire Council meeting, which was held in temporary Council offices in Whalley Chambers on 29th October 1929.

Mr R. Wilson, Chairman of the Town Planning Association, addressed the Councillors. He said that the disaster had presented them with a fine opportunity to improve the town's centre. The approaches to the railway station were not satisfactory, and now they had a chance to make it right and give the town a real focal point. He referred to "the great opportunities that had been taken after the great fires of London and San Francisco, and how fires had enabled Sydney's Circular Quay and Brisbane's Anzac Square to be built. There were exceptional opportunities too, in Nambour, as a result of the fire, for making all of the buildings and streets conform to a correct plan. The first consideration was to work out the whole building scheme to conform with new alignments and levels. There was no need to go on with the whole of the work all at once, but to provide for the complete lay-out in the plan. Then it could be tackled according to the finances available, and added to as funds permitted. He urged them to tackle the job in a proper and thorough way." {1-11-1929, p.3}

It is worthy of note that a gentleman would speak so optimistically for the future after such a catastrophe, particularly as in New York the Wall Street sell-off on the stock market had started on the day of the fire, beginning a world-wide economic crisis. If he had owned a crystal ball, he might have predicted that the devastating Wall Street Crash, known forever as Black Tuesday, actually occurred on the very day of his visit, ushering in the Great Depression. However, the impending Crash was not known at the time, and his optimism was shared by the Councillors, for at that meeting they quickly decided to rebuild the Nambour Town Hall as soon as possible. The new building would be bigger, grander and more impressive than the one they had lost, and it would be named the 'Maroochy Shire Hall'.

Within a week of the Town Hall fire, the Nambour Chronicle was reporting that Mr Gray had met with officials from the Shire Council, as he still held his licence to show pictures, and Nambour had just lost its last cinema. They gave him permission to set up an open-air movie venue on rising ground at the rear of Messrs Hobson and Beale's brick butchers shop in Currie Street. The site backed onto the Moreton Central Sugar Mill, which had nearly finished the year's crush. Mr Gray's friend Edgar Wells co-managed the Returned Soldiers' Garage adjoining Hobson and Beale's on its south side. (Interestingly, in later years another cinema that currently houses Dimmey's bargain store was built on the self-same block of land.) Gray was required to give assurances that the projection box would be away from any buildings and would be thoroughly protected against fire. Mr Gray soon purchased all the seating accommodation required, and all the machinery, including two replacement projectors. {1-11-1929, p.3} {20-12-29, p.8}

He was ready to present his first open-air program by 2nd November, just ten days after the Town Hall fire. The Nambour Chronicle said that "he had a selection of half-a-dozen very fine features for the program on the Saturday evening. It was not expected that he would have the two projectors running, although these had been purchased. The time at his disposal did not permit of the installation of the two machines. In dealing with the construction of the machines, Mr Gray stated that they were of the latest type, and were now made so that nothing short of a miracle would cause a recurrence of the accident that caused the conflagration of last week." {1-11-29, p.3}

Mr Gray screened his open-air movies successfully, but the vagaries of the weather occasionally caused program cancellations. When winter arrived, he hired the Show Pavilion and transported his patrons to the Nambour Showgrounds by bus. When a new Diggers' Hall was opened in Howard Street, he moved his equipment back to town, and resumed programs there in October 1930.

By April 1931 the new Maroochy Shire Hall was completed at a cost of exactly ₤13,645-12-6d. The damaged Kent's Buildings were bought by the Shire Council and auctioned for sale and removal. {8-5-31, p.2} Where they had stood was made into a small park, which became known as Station Square. This provided a public meeting place for civic receptions, and also an open space which enhanced the view of the imposing new Hall. Mr Kent and Chemist Alfred Crofts leased adjoining shops in the Shire Hall's Currie Street frontage, which gave them premises in the town's newest and best building. {27-3-1931, p.2}

At right, Kent and Hook's shop adjoining Alfred Croft's Pharmacy in the new

Shire Hall, 1931. Currie Street was sill a dirt road at the time.

Photograph courtesy Sunshine Coast Libraries

A large auditorium was incorporated into the Hall, and the Shire Council decided that it should be set up as a picture theatre able to screen sound films or 'talkies'. This would require the installation of expensive plant and equipment.

Mr Gray and Mr Wells decided to collaborate, and formed a company called 'Nambour Pictures Limited' with their wives and three other people. By pooling their resources, the partners were able to win the lease of the Hall and install new state-of-the-art Western Electric projection and sound machinery. The Nambour Chronicle of 10th April 1931 ran the final advertisement for movies in the Diggers' Hall ('Metropolis' and 'Sparkling Youth'), and alongside it a second advertisement for the Talkie Opening at the new Maroochy Shire Hall (still described as the 'Town Hall'). Nambour Pictures Limited presented the town's first 'talkie' film, 'Rio Rita' in the new Shire Hall on 18th April 1931. {10-4-1931, p.8} More details about Mr Gray and his cinemas are available here.

The opening of the new Maroochy Shire Hall on 7th April, 1931. Mr Crofts has leased a Chemist

shop on the same spot as he had occupied for 16 years in the old Town Hall,

and indeed for 13 years before that Hall was built, in a small wooden shop.

He had been occupying the site since about 1900. Nambour Railway Station in

background, Station Square at right..

Photograph courtesy Sunshine Coast Libraries

The four-year-old Maroochy Shire Hall in 1935. Station Square as a park is at

lower right..

Photograph courtesy Sunshine Coast Libraries

Footnotes:

1: Despite the danger of fire, the motion picture industry continued to use cellulose nitrate film stock until the 1950s. There were many cinemas burned down, often with numerous fatalities, and there were even some film studios that went up in flames. The introduction in 1948 of cellulose triacetate as a film base, called 'Safety Film', addressed the problem. The new film stock was nonflammable and met the rigorous safety and performance standards set by the cinematographic industry. However, it had its own drawbacks, for over the years it has revealed poor chemical stability by shrinking, developing bubbles, becoming weak and brittle, and releasing acetic acid, the key ingredient in vinegar. Thus, the problem has become known as 'vinegar syndrome', which has now become a major threat for film collections and archives. The only way to save the old movies is to periodically copy them onto new film stock, or to archive them in a high-definition digital format, as on a 4K Blu-ray DVD.

2: Situated on the south bank of the Brisbane River near the old Victoria Bridge, the Cremorne Theatre at South Brisbane was a popular venue for pantomimes, vaudeville, revues, musicals and plays. Opened in 1911, it was wired for sound in 1934 and thereafter also used as a cinema. The Cremorne was destroyed by fire on 18th February 1954, the cause being stated as “the combustion of inflammable film”. The night of the fire was an emotional time for many Brisbane theatregoers. The Courier-Mail stated that an estimated 40 000 Brisbane residents stood and watched the fire destroying the building and causing damage in excess of £100 000. {C-M 19-2-1954} Today, there is a new Cremorne Theatre located on the same site, as part of the Queensland Performing Arts Centre (QPAC).

3: In the 1988 Academy Award winning film 'Cinema Paradiso', there is a realistic depiction of a similar accident to a projector, resulting in an instantaneous fire that burns out the cinema and causes the projectionist to suffer life-threatening burns. The parallels with the Town Hall fire are striking, but such accidents were quite common.

4: Some readers may be interested in viewing the hilarious film 'Speedy', which was shown at the Town Hall a week before the fire. It is Harold Lloyd's last silent film, and includes extensive footage shot in New York City and Coney Island Fun Fair in 1928. This footage is now historic - in particular, the hair-raising rides at Coney Island would give present-day Workplace Health and Safety officials palpitations! In the film's finale, Lloyd drives a horse tram at breakneck speed off the rails and through busy New York city streets including Broadway and Times Square. There was an unscripted accident in which the tram collided with a pillar which supported the elevated railway. This was then written into the script to explain the severe damage visible in subsequent scenes and forms part of the movie. Lloyd went on to make sound movies. 'Speedy' is one of eleven films included in a two-DVD set costing US$ 25.13 plus postage: 'The Harold Lloyd Comedy Collection - Volume 3'. The duration of the individual films varies from 25 minutes to 96 minutes. All of the films are restored and remastered, the worst scratches and other film imperfections have been digitally removed, the speed of the images has been made normal (instead of the fast, jerky motion usually associated with films made at 18 frames per second before the advent of sound introduced 24 frames per second as a new standard), and the silent ones have newly scored and recorded music tracks of high quality. 'Speedy' is available here.

Digital Nambour Chronicle Picture Sunshine Coast